This post is a more detailed version of an article originally published at The Conversation.

The Victorian government has overhauled regulations for site-based permitted clearing of native vegetation, in the first major reform in this area since 2002.

Vegetation management policy rarely makes headlines, but it is important, because native vegetation provides amenity, aesthetics, and vital ecosystem goods and services such as native pasture for forage, shelter for stock, erosion control and nutrient cycling for healthy soils, water purification and habitat for plants and wildlife.

The Consultation Paper attracted over 200 submissions from local councils, statutory authorities, environment groups, industry peak bodies, academics and individuals. The review was welcomed as an opportunity to improve the operation of native vegetation management policy, but the majority of submissions expressed concerns over the new regulations. To the consternation of local government, planners, environmental groups and academics, the new rules were announced in May with no further opportunity for comment.

Scientists have long argued for clear objectives, smarter use of data, models and transparent guidance in environmental decision making. The new regulations seem to answer this call with their detailed step-by-step processes underpinned by a suite of publicly available modelled biodiversity information tools. So why aren’t local councils, landcare groups and scientific communities cheering this? Why the deep unease about these reforms?

Lowering the bar: from “net gain” to “no net loss”

One of the most significant changes is in the stated goal of the native vegetation regulations.

In the original 2002 regulations, the objective was to achieve “a reversal, across the entire landscape, of the long-term decline in the extent and quality of native vegetation, leading to a net gain”. Now, the goal is for “no net loss in the contribution made by native vegetation to Victoria’s biodiversity”.

As members of the community, we understand that the Government has objectives for community development, economic and employment growth, affordable housing and public safety, and native vegetation management policy must balance a range of environmental, social and economic considerations.

But it’s important to remember that the “net gain” objective was adopted in the first place because it was recognised that Victoria has already lost a significant amount of its native vegetation. Incremental loss was continuing, particularly on private land, and native vegetation management was a cost-effective means of protecting the productive capacity of land, the quality of water resources and biodiversity. None of these facts have changed.

Given this context, adopting a goal of “no net loss” in effect, acquiesces to continued long-term decline, instead of aspiring to improve the situation.

Streamlining approvals with risk pathways

“Green tape” will be cut by minimising the need for expert on-site assessment and relying on modelled biodiversity information maps.

Previously, all applications for clearing required on-site assessments by consultants. Now, only those deemed to be “moderate” or “high” risk require comprehensive assessment and matching of clearing to offsets, if rare or threatened species are affected.

“Low” risk applications will be assessed solely using modelled information, and can expect land clearing to be allowed as long as compensatory offsets (also calculated using modelled data) are provided.

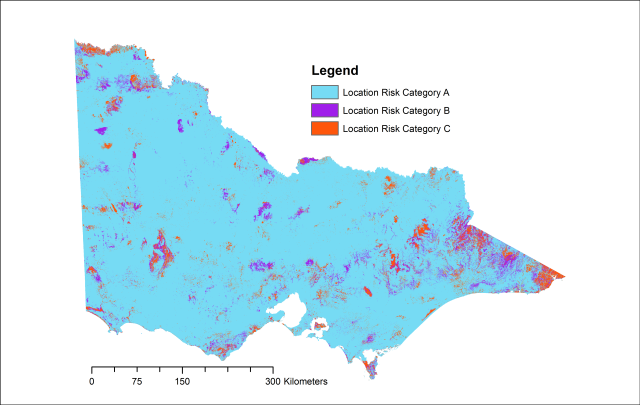

The risk level of an application depends on the size and location of the proposed clearing. All of Victoria has been mapped into three categories (A, B and C) that supposedly reflect “the likelihood that removing a small amount of native vegetation at a location could have a significant impact on the habitat of a rare or threatened species”.

By focusing narrowly on potential impacts to just rare or threatened species, 91% of Victoria ends up in the lowest Location Risk A category (shown in light blue in Figure 1) where clearing is permitted as a right as long as it is less than 1 hectare and offsets are provided.

Figure 1. The modelled Location Risk map for Victoria. [Source: Native Vegetation Regulation (2013) Location Risk version 2 – 25m resolution, DataSearch Victoria http://services.land.vic.gov.au/SpatialDatamart/index.jsp%5D

Biodiversity goes beyond rare and threatened species

Rare and threatened species are important, but this limited interpretation runs contrary to the government’s own definition of biodiversity that includes, “the variety of all life forms, the different plants, animals and microorganisms, the genes they contain and support, and the ecosystems of which they form a part”.

This decision to ignore broadly-defined biodiversity at the risk assignment stage leaves remnant native vegetation vulnerable to being chipped away by permitted clearing and undermines the “no net loss” objective.

This decision is difficult to comprehend because the Government actually has another modelled dataset that provides a better measure of the value of native vegetation for biodiversity across the landscape as a whole. This dataset, the Strategic Biodiversity Score map (Figure 2), takes into account rarity and level of depletion of different vegetation types, species habitats, and condition and connectivity of native vegetation.

![Figure 2. The modelled Strategic Biodiversity Score map for Victoria. (Scores are continuous but have been classified for display purposes) [Source: Native Vegetation Regulation (2013) Strategic Biodiversity Score version 2, DataSearch Victoria http://services.land.vic.gov.au/SpatialDatamart/index.jsp]](https://yungresearch.files.wordpress.com/2013/10/strategic-biodiversity-score_nvr2013_sbsv2.png?w=640&h=405)

Figure 2. The modelled Strategic Biodiversity Score map for Victoria. (Scores are continuous but have been classified for display purposes) [Source: Native Vegetation Regulation (2013) Strategic Biodiversity Score version 2, DataSearch Victoria http://services.land.vic.gov.au/SpatialDatamart/index.jsp%5D

The Strategic Biodiversity score is used to calculate the appropriate compensation (i.e. offset) for proposed clearing, but curiously, isn’t used to assess the risk pathway. This leads to a situation where high quality native vegetation with high Strategic Biodiversity scores can nevertheless end up classed as Location Risk A, and be susceptible to small-scale clearing.

Oversights, errors and their consequences

While the regulations make smarter use of data, technology and sophisticated modelling to support decision making, steps crucial to the credibility of these tools have been missed in the haste to implement these reforms.

For instance, some of the rare or threatened species included in the construction of the biodiversity information maps include environmental weeds (e.g. Acacia howitii, Melaleuca armillaris subsp armillaris), ornamental (e.g. Corymbia maculata) and plantation (Eucalyptus globules subsp globules) species.

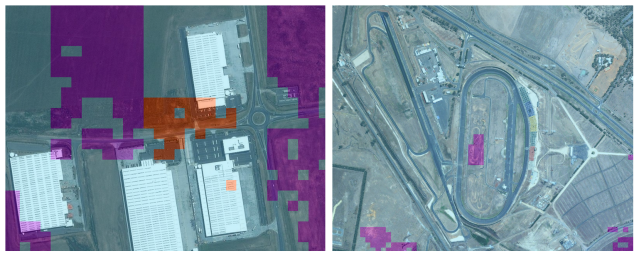

The accuracy of the modelled maps at the intended scale of use is crucial. But a closer look throws up some worrying surprises. For example, car parks and construction areas within the grounds of Melbourne Airport and the infield parking and viewing area within Calder Park Raceway have been classified as high risk categories B and C (Figure 3).

Figure 3. On the left, car parks and construction areas within Melbourne Airport grounds have been classified as Location Risk B (purple) and C (orange). On the right, parts of Calder Park Raceway have been classified as Location Risk B (purple). [Source: ArcGIS satellite World Imagery map service (http://www.arcgis.com/home/item.html?id=10df2279f9684e4a9f6a7f08febac2a9) overlaid with Native Vegetation Regulation (2013) Location Risk version 2 – 25m resolution, DataSearch Victoria http://services.land.vic.gov.au/SpatialDatamart/index.jsp%5D

Conversely, well-documented locations of high conservation value threatened flora and fauna in areas like Bungalook Conservation Reserve in Kilsyth South and the Dandenong Ranges National Park have inexplicably, been classed as Location Risk A. These are unlikely to be isolated instances.

Instead of experiencing greater certainty and efficiency, proponents seeking to clear native vegetation that is not genuinely rare or threatened, or which has been misclassified as “high” risk, may face being unfairly burdened with excess costs in assessment and offsets.

In a similarly perverse way, permitted clearing of high conservation value native vegetation that is misclassified as “low” risk becomes a cost borne by the wider community.

What’s behind the mapping errors?

Compounding the problems with assignment of risk-pathways, there are known problems with the input data used to build the models:

• species occurrence data is heavily biased towards public land – common landscapes that are poorly represented include arable, lowland areas that are predominantly freehold

Ironically, this means our knowledge of biodiversity is poorest and possibly most error-prone, in freehold areas that are most depleted in native vegetation and also most likely to be subject to applications to clear for urban development and agricultural intensification.

• historically, the various species databases managed by the State have been chronically under-resourced, resulting in uneven data capture, lack of quality control and assurance and database maintenance and updating

• species location records can vary in accuracy from 10s to 100s of metres

The base species habitat suitability maps built from these data have a spatial accuracy of 225m. However, the biodiversity information maps derived from these base maps claim a much higher spatial accuracy of 25m or 75m. Since ‘child’ datasets cannot have a true spatial accuracy that is higher than that of it’s coarsest ‘parent’, the actual spatial accuracy of the modelled maps may not be fit-for-use at the scale of application intended by the regulations.

Where do we start to fix the new system?

First, to ensure coherence between the permitting process and the stated goal of the regulations, the assignment of risk pathways must take into account not only potential impacts on rare and threatened species, but also impacts on the value of native vegetation for broadly-defined biodiversity.

Errors are neither unexpected nor unusual given the complexity of using data from many forms and sources to model biodiversity information for a ~227,700 km2 state. But we can have more confidence in the permitting process if it includes mechanisms for procedural fairness and processes for handling inevitable errors and problems.

A good start can be made by: a) addressing data deficiencies on freehold land; b) conducting independent peer review and quality assurance testing by end-users such as local councils and planning authorities; c) providing avenues for error-reporting and d) committing resources to quality assurance, improvement and regular updating of the biodiversity information maps.

Many of the submissions from local councils, community environment groups, industry peak bodies, consultants and academics took pains to explain the basis of their concerns with the new regulations and propose constructive measures for improvement. (see for example, submissions from MAV, LGPro, Goulburn Valley Environment Group, Brett Lane & Associates and RMIT University)

There are real opportunities to make improvements to the operability of clearing regulations that will also result in better environmental outcomes. But these can only be realised if the Victorian government is willing to properly address the concerns and solutions raised in the submissions from the wider community.